“There are only two things you can’t do online in Estonia: get married or get divorced,” That was the third thing that Daniel Schaer, Estonia’s ambassador-at-large for economic cooperation in Africa, said to me.

The first thing was, of course, introductions. The second, helpfully pointed out by someone else, was that Ambassador Schaer was wearing a wooden bow-tie. They both encouraged me to touch it to believe it, which I did but quickly stopped when it occurred to me that breaking it might be the beginning of a diplomatic incident.

So instead we shifted the conversation to Estonia’s claim to fame in a space that has historically been resistant to change, governance, and its digital society, e-Estonia.

E-government, the provision of vital government services through digital platforms, is one of the most revolutionary possibilities of living in the digital age. In an increasing number of countries, it is now possible to get many government services without having to visit a physical office.

The sales pitch for bringing government services is obvious-it reduces costs, enhances inclusion, helps curb corruption, and just makes everyone’s work and life easier. E-tax platforms, for example, mean that you no longer have to queue to file your taxes, or to dedicate hours of labour to the task.

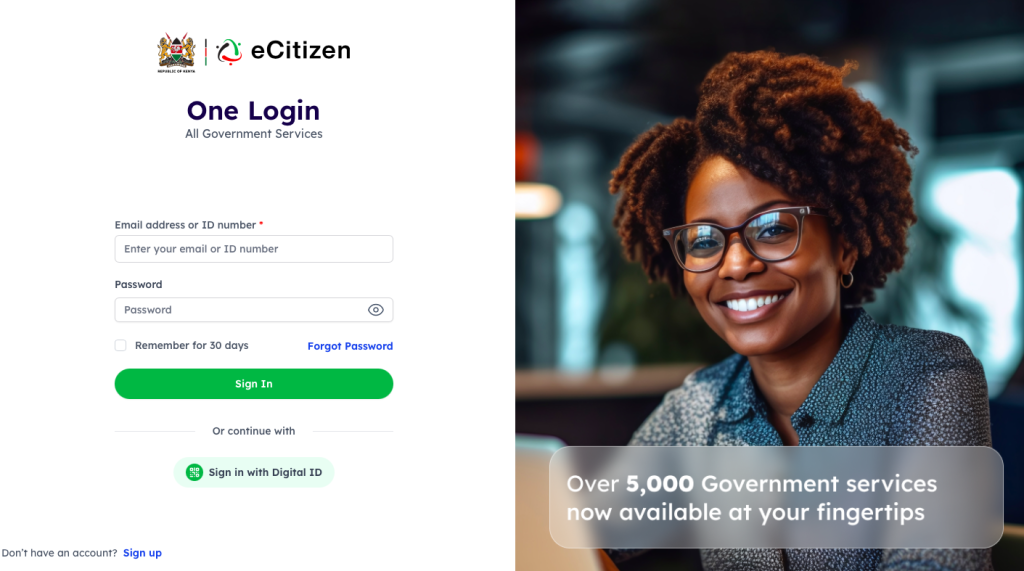

In Kenya, you can check company records, process your passport and visa applications, and get more than 5, 000 other services on the e-government platform E-citizen. While its interoperability has improved, it still far behind its potential to reshape how citizens interact with the government and critical services provided by the private sector.

As of 2023, only 7 of 47 counties are linked on the platform.

“There are three ways of identifying yourself,” Schaer, who recently presented his credentials as Estonia’s first ever ambassador to Kenya, said in a later conversation, “that’s an ID card, a SIM card, or a smart app.” The ID card system works such that one number is assigned at birth, and follows you for the rest of your life.

The X-Road to e-government

To solve the separate databases problem and the inherent cost element that comes with it, Estonia created an interoperability system called X-Road which also facilitates public and private databases to interact in real time.

The result is that 99 percent of public services are available online 24 hours a day. “Estonia saves 2-3% of GDP per year, and a pile of paper the height of the Eiffel Tower,” Schaer says proudly. By their estimate, every Estonian saves two to three weeks that would have been spent waiting in queues for services.

This includes health emergencies and hospital visits, because the system also has individual citizen’s medical history and data. This health data can be accessed by paramedics through an app, and is also used for telemedicine.

In 2005, Estonia held elections over the internet, and in 2014, begun offering e-residency. Interestingly, and importantly, the move to allow citizens to vote online actually begun within government, where a paperless e-Cabinet system allows politicians and bureaucrats to conduct government business online.

Instead of cabinet meetings taking hours and lots of travel (and recently in Kenya, timekeeping), Estonia’s politicians and bureaucrats could now get things done online in 5 mins.

Perhaps they’d save more time if they could get married and/or divorced online as well, but for such major life decisions, the Estonian government prefers a bureaucrat look you in the eye, in broad daylight, and ask if both of you are sure.

I wouldn’t be surprised if they also have an unnecessary queue and unnecessary papework, just to give you and your partner some more time to really decide if you want to involve the government.

Kenya now plans-and just recently postponed the launch of-a new ID in the form of Maisha Namba, which is the most recent iteration of Huduma Namba, which was declared unconstitutional in 2021.

Similar to the ID card that already exists, these new iterations are issued at 18, and anyone below that age moves around life with a birth certificate as the only unique identifier. But tax experts also recently recommended that every person be assigned a distinct tax identifier at birth.

Given other unique identifiers we already use, such as passport number, student ID number, driving license number etc, the future looks too similar to the present.

When Estonia gained independence in 1991, it was faced with several major challenges. Among the first solutions it sought, leapfrogging even the countries that were integral to building the internet, was how to better offer government services.

It had some incidental advantages that resonate with Kenya’s mobile revolution: Since very few people had landline phones during Soviet occupation, it was easy to leapfrog to mobile phones, and since the Soviets did not introduce cheques, Estonians moved directly to bank cards.

Startup heaven

One interesting result of this forward-thinking governance is that for a country with a smaller population than Kakamega County, Estonia has produced as many unicorns as the entire African continent has today.

Skype was built by, among others, three Estonian developers, before they flipped it to e-Bay, who then sold it to Microsoft for $8.5 billion.

Estonians founded, or were also primary engineers in Transferwise (now Wise, whose founder had been Skype’s first employee), Bolt, ID.me, Gelato, Veriff, Playtech. Two of these, Veriff and Glia, were ‘minted’ as unicorns in 2022 alone.

In total, Estonia has 1 startup for every 1, 000 people, and now plans to have 25 unicorns by 2025.

There’s a lot that makes this small country a haven for startups, including 60 double taxation treaties, 0% income taxes on retained and reinvested profits e.t.c. “Where else could you establish a startup online in 15 minutes and file tax returns in a jiffy with just a few mouse clicks?” Eve Peeterson, head of Startup Estonia, asked at an event in March 2022.

There have, of course, been challenges. The foremost challenge of e-government, and any digital platform that carries private information, is trust.

Estonia got lucky. Among the earliest supporters and users of the e-government services were banks because it made business sense. It, for example, reduced their KYC costs. Estonia also had to make sure from the onset that there were critical services attached to the system, which is where banks early adoption came in handy, and that the services were applicable to the people.

The second is that citizens own all their data. Schaer says that citizens can remove their own data, which includes medical history. Police officers must have a legal reason for checking a particular citizen’s information.

Sometimes, a queue is not just a queue

It has been three decades of this e-government system, so Schaer is open about the challenge that legacy infrastructure now poses, especially as access technologies get better.

Estonia is currently assisting Benin and Namibia with interoperability, and in Nigeria, an Estonian company built the budget management system. Estonia’s e-gospel is essentially this, that databases in silos is a challenge because databases that can’t speak to each other make life harder when it shouldn’t be.

Among its challenges on the continent is, of course, defining what this concept is and why it needs such massive investments. Bureacracies provide employment, rent offices and allow people to deal with human beings directly, as opposed to through an interface.

But the digital revolution has already disrupted many of these underlying notions in Kenya, where probably the only thing you can’t pay for via MPESA (anymore) is a bribe, and that’s more about paper trail and the practicalities of corruption than possibility.

But Schaer tells me of a minister from the continent who told him that we don’t mind queuing because that’s where we get to talk about what’s happening in the country.

There’s some truth to that, but the future of e-government looks a lot like Estonia’s.