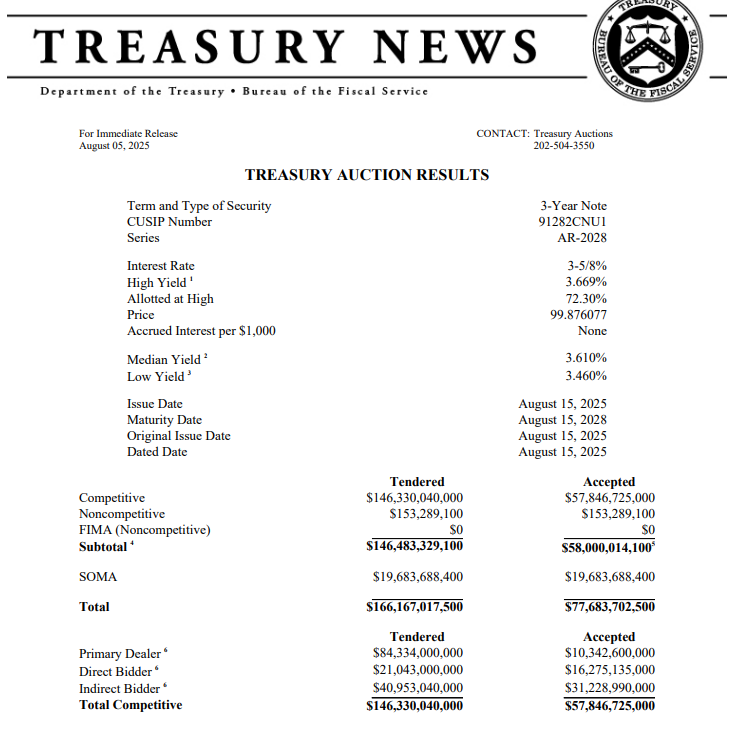

The U.S. Treasury’s August 5th auction of 3-year notes aimed to raise US $58 billion, and received competitive bids of US$ 146.3 billion.

- •On the surface, the target was met, but a closer look at the buyer composition reveals something more telling, that investor participation fell short of typical levels.

- •The decline in foreign demand should be viewed as part of a broader evolution in global capital allocation.

- •Key U.S. creditors are actively diversifying their reserves, turning toward gold, regional currencies, and domestic infrastructure investment.

Although the headline numbers may not indicate a crisis, the composition of demand speaks volumes. The yield on the note was 3.669%, relatively attractive in historical context. Yet the auction saw foreign buyers take up just 54% of the accepted bids, the lowest share in over a year. These indirect bidders, who typically include most foreign governments and global investors, have traditionally formed the core of demand for U.S. Treasuries.

Rising FX hedging costs have made it less attractive for foreign investors to hold U.S. debt. In many cases, the return on hedging against dollar risk has fallen close to zero, eroding one of the key advantages Treasuries have historically offered.

With foreign appetite cooling, US-based investors took a near-record 28% of the auction, a sharp increase in domestic participation. Primary dealers, who provide underwriting support for Treasury sales, absorbed 18%, a-less-than-ideal outcome, as healthy auctions typically see lower dealer take-up. These shifts point to a growing reliance on the domestic investor base to sustain U.S. debt issuance.

At the same time, global yield differentials are narrowing. With developed markets like Japan and parts of the Eurozone now offering sovereign yields in the 2-3% range, the traditional yield premium of U.S. Treasuries is no longer as compelling- especially when combined with the rising cost of hedging and growing uncertainty around U.S. fiscal governance.

This gradual repositioning, though often overlooked, reflects a changing world order in which reliance on U.S. financial instruments is becoming less attractive.

What This Means for Global Markets is Multifaceted

If foreign participation in U.S. debt continues to decline, it could place upward pressure on yields, forcing the U.S. to offer more attractive terms to lure investors. That, in turn, raises the cost of borrowing not just for the U.S. government, but also for corporates and households, given Treasuries’ benchmark role in global pricing.

Sustained weak demand could add volatility to emerging market debt and FX markets. Many developing economies are sensitive to fluctuations in U.S. yields and dollar liquidity. If investors perceive U.S. assets as riskier or less rewarding, capital may rotate into local or regional markets, heightening currency instability and tightening financial conditions for economies already grappling with debt sustainability.

In addition, there are macroeconomic signaling risks. Treasuries are not just financial instruments, they are also read as indicators of global confidence in the U.S. economy and political system. A weakening signal here can feed into wider risk sentiment, affecting everything from equity risk premiums to global liquidity flows.

The fact that demand for longer-dated Treasuries, such as the upcoming 10- and 30-year auctions, remains steady is a stabilizing factor for now. These instruments reflect long-term expectations on growth and inflation, and as such, continued strength there indicates that investors still see value in the U.S. debt at the macro level.

However, the 3-year note sits at the intersection of short term Fed policy and medium-term fiscal credibility. If upcoming auctions reflect similar weakness, it may indicate that investor caution is extending to longer maturities, making it harder to attribute the trend to short-term or technical factors.

This was a telling auction. The U.S. still sits at the centre of the global financial system, yet the composition of demand in auctions like this points to a slow but meaningful shift in the underlying structure. If foreign capital continues to pull back, whether driven by the economy, strategy, or geopolitics, the ripple effects across asset prices, central bank repositioning, and cross-border liquidity could be more far-reaching than they currently appear.