Originally by Nick McCullum & Ben Reynolds. Updated on August 29th, 2022 by Bob Ciura for SureDividend

Capital allocation is perhaps the most important job of an established company’s management team…

But what exactly is capital allocation?

Capital allocation is the process of distributing an organizations financial resources.

The purpose of capital allocation in publicly traded corporations is to maximize shareholder returns.

This article covers all 5 methods of capital allocation. The 5 methods of capital allocation are listed below:

- •Investing in organic growth

- •Mergers & acquisitions

- •Paying down debt

- •Paying dividends

- •Share repurchases

You can learn about each of these principles in the following video:

Capital allocation has a profound effect on long-term investment returns.

Where management decides to spend money ultimately determines how quickly the company will grow and how much money is returned to shareholders.

Case-in-point: some of the most successful CEOs (as measured by the per-share increase in their company’s intrinsic value) have viewed themselves primarily as capital allocators.

Several CEOs (both current and historical) famous for their excellent capital allocation skills are below:

- •Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A) (BRK.B)

- •Jeff Bezos of Amazon (AMZN)

- •Henry Singleton of Teledyne Technologies

- •Tom Murphy of Capital Cities

- •Bill Anders of General Dynamics (GD)

As shareholders, it is our job to ensure that management is making intelligent decisions for capital allocation. We must therefore understand the impact of various capital allocation techniques.

Keep reading to see detailed analysis on each of the five methods of capital allocation.

Investing In Organic Growth

When investing for organic growth managers opt to reinvest excess capital into the operating business that originally generated it.

Examples of organic growth investments include:

- •Research and development

- •Building out the supply chain

- •Launching a new product service

- •Improving an existing product or service

The decision on whether or not to reinvest funds is dependent on two factors:

- •Capacity: How much capital can reasonably be reinvested per unit of time before diminishing returns occur

- •Business unit profitability: Generally measured by return on invested capital, this shows the return that can be expected on any reinvested capital

Business unit leaders can proxy the returns from organic reinvestment by multiplying their reinvestment rate by the business’ return on capital. So if a business reinvests 50% of capital at a 20% ROIC, then a 10% return can be expected.

Investing for organic growth is primarily a long-term strategy. Many of the best growth investments pay off in years, not months.

One of the best capital allocators who primarily uses both a long-term approach and reinvesting for organic growth to increase shareholder wealth is Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon.https://www.youtube.com/embed/ppe94FFSNP0

It is important to keep in mind that many businesses have no choice about whether or not to reinvest.

Some businesses are so capital-intensive that almost all operating cash flow must be reinvested just to maintain their current competitive position. Since capital must be continuously reinvested to maintain the business, there is no excess capital to fund more aggressive growth projects or diversify the enterprise’s operations. This makes capital-intensive businesses less-preferred to capital-light businesses, all other things being equal.

Warren Buffett once mentioned the airline industry as an example of a sector with these characteristics, although his opinion apparently temporarily reversed when Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio showed a significant stake in the 4 major U.S. airlines, which have since been sold.

“Now let’s move to the gruesome. The worst sort of business is one that grows rapidly, requires significant capital to engender the growth, and then earns little or no money.”

– Warren Buffett in Berkshire Hathaway’s 2007 Annual Report

A business that requires very little reinvestment (although reinvestment is certainly an option if growth prospects are bright) is preferable. Capital-light business models with minimal reinvestment requirements make fantastic investments because they offer more optionality.

In other words, it is up to the management team – rather than the economics of the business – to decide whether organic reinvestment is the path to building long-term shareholder value.

Berkshire Hathaway’s decentralized operating structure with Buffett & Munger acting as capital allocators is one example of the fantastic use of the capital-light characteristics of various industries.

The following Munger quote illustrates why.

“We prefer businesses that drown in cash. An example of a different business is construction equipment. You work hard all year and there is your profit sitting in the yard. We avoid businesses like that. We prefer those that can write us a check at the end of the year.” – Charlie Munger at the 2008 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Meeting

Importantly, a capital-light business does not need to have strong organic growth prospects in order to make a compelling investment.

For example, if you could buy an 8% yielding bond from a AAA-rated company, you would jump at the opportunity. While the fixed income security has zero growth prospects (coupon payments are constant over time), its combination of high returns (8% yield) and low risk (AAA credit rating) make it a compelling long-term investment.

The same logic applies to the ownership of full operating businesses. A stagnant business can make a solid investment if:

- •It generates excess free cash flow that can be invested elsewhere

- •Its competitive position is strong and unlikely to deteriorate in the near future

Again, Berkshire Hathaway is a phenomenal example of a company that sometimes purchases slow-growing businesses because of their ability to generate high levels of excess cash flows that can be reinvested in other growth projects.

In fact, Warren Buffett once warned about the perils of mindlessly investing money back into the company that generated it:

“Long-term competitive advantage in a stable industry is what we seek in a business. If that comes with rapid organic growth, great. But even without organic growth, such a business is rewarding. We will simply take the lush earnings of the business and use them to buy similar businesses elsewhere. There’s no rule that you have to invest money where you’ve earned it. Indeed, it’s often a mistake to do so: Truly great businesses, earning huge returns on tangible assets, can’t for any extended period reinvest a large portion of their earnings internally at high rates of return.” – Warren Buffett in Berkshire Hathaway’s 2007 Annual Report

While organic reinvestment is likely the most straightforward capital allocation strategy employed by corporate executives, it is not always the best.

The next section discusses a more complicated capital allocation strategy – mergers & acquisitions.

Mergers & Acquisitions

Mergers & acquisitions are some of the most transformative – and risky – capital allocation moves that corporate executives can make.

An example of allocating capital towards an acquisition is buying a business. Alternatively, a company’s management may elect to merge with another company, or spin-off a business line to generate cash that can be put to better use elsewhere.

Because of the additional risk assumed through acquisitions, there is a great divide among investors as to the efficiency of mergers & acquisitions as a growth strategy.

The data suggest that M&A is a viable capital allocation strategy. More specifically, companies classified as ‘serial’ acquirers tend to have the best performance.

Acquirers tend to underperform when markets are at all-time highs.

Intuitively, this makes sense. When markets are high, it is more likely that the acquiring company is overpaying for its purchases, which reduces future total returns. This holds true whether buying an entire operating business or purchasing a fractional ownership through common shares.

The value-creating capabilities of mergers & acquisitions are different depending on the terms of the deal in question. An acquisition that may make sense at one price will eventually become foolish if prices are sufficiently increased.

Because of this pricing phenomenon, it is difficult to make generalized statements about the efficiency of this capital allocation strategy.

Instead, investors should review individual mergers & acquisitions of a management team, rather than blindly accepting them as a strong use of capital.

Paying Down Debt

Of all capital allocation techniques that corporate executives employ, debt repayments are certainly the most predictable.

This is primarily because the return on repaid debt is known in advance.

Since the vast majority of corporate debt is issued as publicly-traded fixed income securities, their yields to maturity can be mathematically computed.

Repaid – or repurchased – debt will always have a return that is equal to its yield to maturity based on prevailing fixed income market prices.

Just because debt repayments are a predictable capital allocation strategy does not mean that they are an attractive capital allocation strategy.

When interest rates are low, companies are generally better off not repaying debt early. Or, to take advantage of lower rates, debt may be refinanced at lower rates in a low interest rate environment.

Conversely, sky-high interest rates incentivize corporations to repay debt before maturity, as refinancing bonds at higher rates will lead to material increases in interest expenses.

Thus, the decision of whether to repay debt is highly dependent on prevailing interest rates. Accordingly, the amount of corporate debt outstanding varies inversely with interest rates.

In the financial crisis, when rates were cut, corporate credit levels increased significantly for a short period of time before returning to normal levels. Since then, debt has continued to creep upwards as more and more corporations take advantage of the economy’s cheap monetary supply.

Corporations have great opportunities to build shareholder value by issuing debt when interest rates are low. It can make sense to take advantage of low interest rates and use funds from cheap debt to invest in higher expected return opportunities. This strategy will be discussed in the following two sections.

Paying Dividends

Dividend payments form the core of much of what we do at Sure Dividend. In fact, dividend yield is one of the factors in The 8 Rules of Dividend Investing, our quantitative ranking system for dividend stocks.

We believe dividend stocks offer a compelling risk-reward proposition for individual investors.

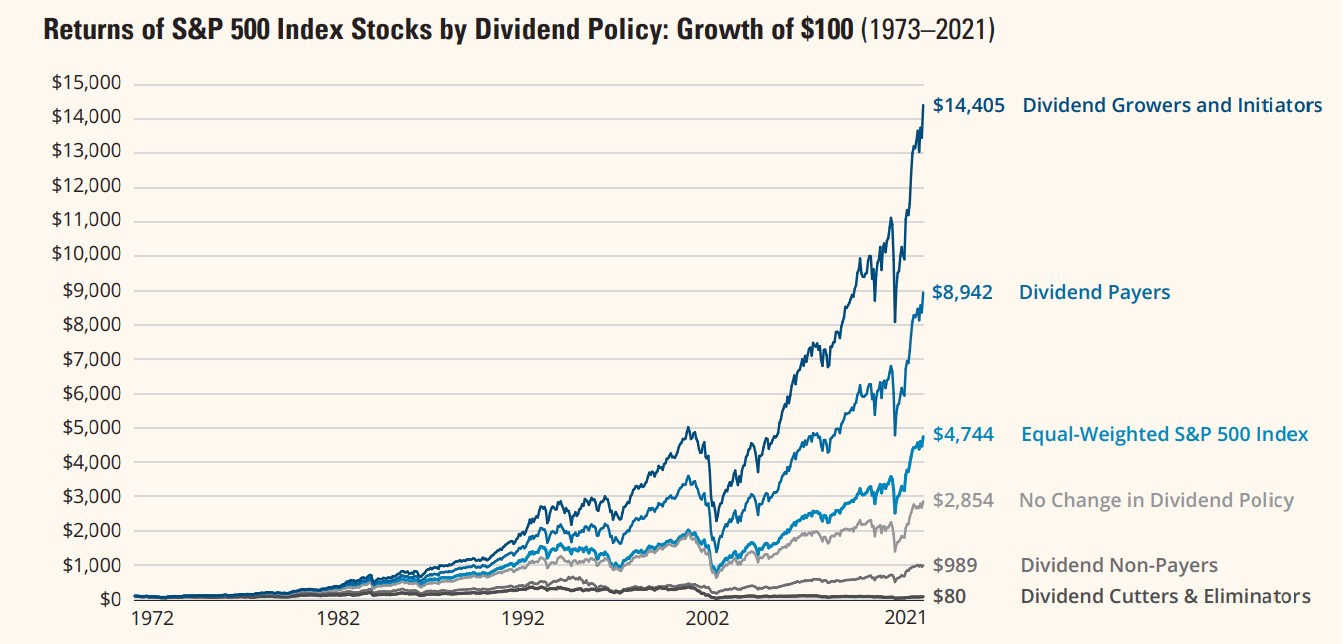

Importantly, dividend growers and initiators outperformed especially, and dividend stocks in general, have exhibited long-term outperformance according to the image above.

You can find high quality dividend growth stocks using the lists below:

- •The Dividend Aristocrats: 25+ years of consecutive dividend increases

- •The Dividend Kings: 50+ years of consecutive dividend increases

- •The Dividend Achievers: 10+ years of consecutive dividend increases

With that said, there are plenty of non-dividend stocks that have delivered tremendous outperformance over long periods of time, including Berkshire Hathaway and technology companies like Amazon.

Instead, dividends are a sign of a high-quality, shareholder-friendly business. It means that corporate executives have a laser-focus on shareholder value and understand that it is the shareholders – not the executives – that ultimately own the companies.

This belief is corroborated by many world-class investors, including Benjamin Graham, who wrote the following in his book ‘The Intelligent Investor’:

“One of the most persuasive tests of high quality is an uninterrupted record of dividend payments going back over many years. We think that a record of continuous dividend payments for the last 20 years or more is an important plus factor in the company’s quality rating. Indeed the defensive investor might be justified in limiting his purchases to those meeting this test.”

It should also be noted that dividends are a tax-inefficient method for generating total returns.

This is because dividends are taxed twice, first at the corporate level and then at the personal level.

Note: REITs and MLPs avoid double taxation thanks to their unique corporate forms.

Thus, it is mathematically better for shareholders for a company to not pay a dividend, assuming the corporation still has ample opportunities to deploy its internally-generated cash. For non-dividend-paying stocks, if an investor needs to generate income from his portfolio, they can periodically sell shares for that reason.

Unsurprisingly, Warren Buffett has long been a proponent of this strategy, noting that the tax implications will result in superior long-term returns. His reasoning can be seen below.

“We’ll start by assuming that you and I are the equal owners of a business with $2 million of net worth. The business earns 12% on tangible net worth – $240,000 – and can reasonably expect to earn the same 12% on reinvested earnings. Furthermore, there are outsiders who always wish to buy into our business at 125% of net worth. Therefore, the value of what we each own is now $1.25 million.

You would like to have the two of us shareholders receive one-third of our company’s annual earnings and have two-thirds be reinvested. That plan, you feel, will nicely balance your needs for both current income and capital growth. So you suggest that we pay out $80,000 of current earnings and retain $160,000 to increase the future earnings of the business. In the first year, your dividend would be $40,000, and as earnings grew and the one-third payout was maintained, so too would your dividend. In total, dividends and stock value would increase 8% each year (12% earned on net worth less 4% of net worth paid out).

After ten years our company would have a net worth of $4,317,850 (the original $2 million compounded at 8%) and your dividend in the upcoming year would be $86,357. Each of us would have shares worth $2,698,656 (125% of our half of the company’s net worth). And we would live happily ever after – with dividends and the value of our stock continuing to grow at 8% annually.

There is an alternative approach, however, that would leave us even happier. Under this scenario, we would leave all earnings in the company and each sell 3.2% of our shares annually. Since the shares would be sold at 125% of book value, this approach would produce the same $40,000 of cash initially, a sum that would grow annually. Call this option the “sell-off” approach.

Under this “sell-off” scenario, the net worth of our company increases to $6,211,696 after ten years ($2 million compounded at 12%). Because we would be selling shares each year, our percentage ownership would have declined, and, after ten years, we would each own 36.12% of the business. Even so, your share of the net worth of the company at that time would be $2,243,540. And, remember, every dollar of net worth attributable to each of us can be sold for $1.25. Therefore, the market value of your remaining shares would be $2,804,425, about 4% greater than the value of your shares if we had followed the dividend approach.

Moreover, your annual cash receipts from the sell-off policy would now be running 4% more than you would have received under the dividend scenario. Voila! – you would have both more cash to spend annually and more capital value.”

Source: Warren Buffett in the 2012 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report

While this explanation is lengthy, it shows that dividends are not the only way (and certainly not the most tax-efficient way) for shareholders to generate portfolio income.

With that said, dividend stocks have historically outperformed. The appeal of allocating capital to dividend payments is that it guarantees shareholders generate an actual cash return.

Share Repurchases

Share repurchases (also called share buybacks) are likely the most misunderstood capital allocation policy adopted by corporate managers.

They are also one of the most powerful if executed properly.

Share repurchases occur when a company buys back its own shares, reducing the number of shares outstanding. This has the beneficial effect of improving important per-share financial metrics such as earnings-per-share, book-value-per-share, and free-cash-flow-per-share.

With that said, the impact of share repurchases is completely dependent on the price that the company pays for its shares.

Ideally, a company will buy back its stock when it trades at low valuations (based on multiples of earnings, book value, or cash flow), and cease buybacks when valuations rise.

To understand why the price of repurchased shares is important, consider the following quote from Berkshire Hathaway’s 2016 Annual Report:

“Consider a simple analogy: If there are three equal partners in a business worth $3,000 and one is bought out by the partnership for $900, each of the remaining partners realizes an immediate gain of $50. If the exiting partner is paid $1,100, however, the continuing partners each suffer a loss of $50. The same math applies with corporations and their shareholders. Ergo, the question of whether a repurchase action is value-enhancing or value-destroying for continuing shareholders is entirely purchase-price dependent.”

– Warren Buffett in Berkshire Hathaway’s 2016 Annual Report

Clearly, the price that a company pays when it buys back stock is very important.

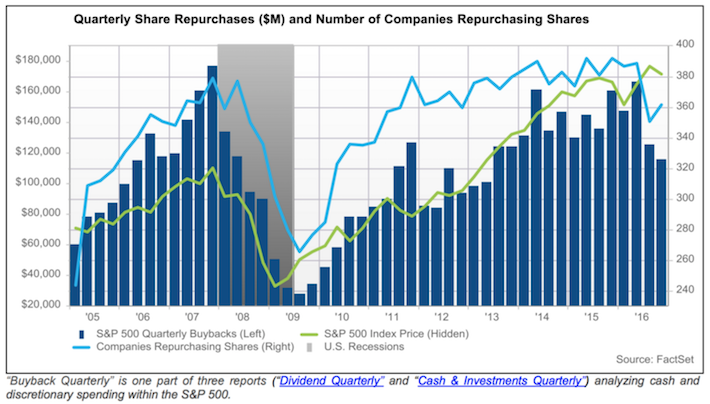

This suggests that companies should be buying back the most stock during recessions when stock prices trade lower than their normal levels. That is not usually the case.

As we know, humans are not always rational. This applies to even the most seasoned corporate executives. During recessions, earnings downturns and operational difficulties lead executives to hoard cash and reduce expenditures wherever possible – including share repurchases.

As a result, share repurchases tend to decline during a recession, as shown below.

Source: FactSet’s Buyback Quarterly

As you can see, share buybacks peaked in 2007 at market highs, then collapsed during the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

This phenomenon is the opposite of what should happen in an ideal world. Any company whose management has the discipline to buy back cheap stock during a recession should be appreciated by its investors.

But what if the company is short on cash, and cannot fund a meaningful share repurchase program?

Buybacks financed with debt have the potential to build tremendous shareholder value. This is particularly true if interest rates are low and if the company pays a dividend.

Repurchasing dividend stocks is more meaningful than repurchasing non-dividend stocks because of the future savings that result from paying less in dividends on a reduced share count.

In addition, the tax deductibility of interest payments means that even if the additional interest expense is slightly higher than the dividend savings, the corporation may be slightly better off on an after-tax basis.

All said, share repurchases have the potential to build tremendous shareholder value if they are executed at a price below intrinsic value. Companies that can repurchase their high yield common shares using cheap debt magnify the benefits of this capital allocation strategy.

The YouTube video here covers share buybacks in depth:

Final Thoughts

The capital allocation choices of any publicly traded business fall into the following five categories:

- •Mergers and acquisitions

- •Invest in organic growth

- •Repurchase shares

- •Pay down debt

- •Pay dividends

Understanding the value-building capabilities and tax implications of each individual strategy is important, whether you are a common stock investor or a seasoned corporate executive.

For corporate executives, understanding capital allocation likely means better returns on a per share basis for shareholders. And investors who understand capital allocation can find management teams that make intelligent capital allocation decisions, while avoiding investing in companies who make mediocre or worse capital allocation decisions.

This article was first published by Nick McCullum & Ben Reynolds for Sure Dividend

Sure dividend helps individual investors build high-quality dividend growth portfolios for the long run. The goal is financial freedom through an investment portfolio that pays rising dividend income over time. To this end, Sure Dividend provides a great deal of free information.

Related:

10 Things To Look For In A Dividend Portfolio Management Tool