Dejected and deflated, Kennedy Waweru sits outside his clothing store at Gikomba Market, Kenya’s largest trading centre, located a few metres from Nairobi’s Central Business District. In the past year, he has closed four of his five shops due to what he calls “Chinese interference”.

Mr Waweru remembers when he periodically traveled to Guangzhou, a sprawling port city northwest of Hong Kong on the Pearl River, to import clothes popular with Kenya’s upwardly mobile customers.

Things were easy for him then. They are not easy anymore.

Visa restrictions, along with government policies that have failed to protect small and medium-sized businesses, have crippled what was once a promising source of income, one that employed scores of Kenyans while supporting hundreds indirectly.

“Thanks to Chinese interference, the business environment here is no longer favourable to me. The way things are right now I cannot compete with them,” Mr Waweru said, blankly staring at potential consumers whisking by without a glance at his direction.

Gikomba Market, which opened in 1952, is a major source of income for thousands of Kenyans who import second-hand goods—from clothing to household items and logistic services. According to the Nairobi Importers and Small Traders Association (NISTA), 90 percent of goods sold there come from China.

About 5,000 small-scale traders have closed shops in the past one year due to the “Chinese invasion,” says the Kenya World Wide Importers and Traders Association (KWITA).

“These are young men who sought alternative sources of income by becoming small-scale traders. Now, most of them cannot afford food or pay for their children’s school fees. A number of them have committed suicide,” said KWITA Chairman Ben Mutahi.

The 35-year old Waweru, a father of four, set up his business six years ago as “there was no employment opportunity” despite his being a Bsc Commerce University of Nairobi graduate. Now, he has to compete with the “China people,” who not only have become major import brokers but also are setting up stalls to compete with the locals.

“They are even selling clothes with us. Can you imagine…they are setting their shops next to ours. They are getting bolder day by day, and they are selling cheap,” he adds with a tinge of bitterness.

After setting up his business at Gikomba market in 2013, Mr Waweru routinely net Ksh2 million. And that was in a “bad month.” He employed 15 permanent staff in his five shops, and had over 60 direct agents for his import business. He says the presence of the Chinese has seen his business nosedive, and since 2016, he can hardly meet Ksh100, 000 in gross sales per month.

“After all these years of self-employment, and sustaining other families, I was left with no option than to close down the import business and my shops. I am heavily indebted with banks and auctioneers knocking down on my doors everyday. I can’t afford to run any business here (Gikomba) anymore,” he says pensively.

Since Kenya began amassing loans from China to build ambitious infrastructure, including the Standard Gauge Railway, the Chinese have become a permanent fixture in the country, running roughshod over many Kenyan businesses, especially in the engineering and construction sectors.

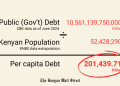

This includes the $3.233 billion debt from China’s Exim Bank to finance the Mombasa-Nairobi railway, which experts say will never break even, despite policies that restrict cargo transportation through it.

China’s share of Kenya’s bilateral debts stood at $8.78 billion by December 2018, according to latest data filings by National Treasury. This represents 70.71 per cent of total value of bilateral debts that Kenya has accrued. The debt-trap is seen as one reason the government is unwilling to address the influx of Chinese influx onto local business scene.

A Kenyan wishing to travel to China as a trader needs an invitation letter, a hotel booking, flight bookings and a letter from the factory or warehouse he or she intends to visit. The trader also needs to submit invoices for previous purchases made.

“A Chinese traveling to Kenya only needs to pay for the flight and apply for a visa without any requirements attached to the application. Hence the bilateral trade relations are not equal,” said Mr Mutahi.

A visit to Guangzhou and Shenzhen, Chinese importation havens for Kenyans, revealed the increasing difficulties and restrictions in conducting their legitimate businesses. They say Chinese authorities target them because they are Kenyans.

Here you will find everything that can be imported from many industrial parks around different districts in Guangzhou. There are factories and manufacturers that deal in apparels, steel, glass, kitchenware, electronic, medical equipment, furniture, and car parts.

The wholesale markets, located in almost every corner of the city, leaves one spoilt with choice. Kenyan buyers go to the Haizhu District for clothing goods, Yuexiu District for ladies wear such as shoes, and Baiyun District for handbags.

Huaqiangbei, a very large market in Shenzhen, is the go-to place for electronics.

In these areas, many Kenyans work in businesses such as clearing and forwarding; translation; and hotels and other lodging. They are the people traders wishing to import their goods rely upon for a seamless transaction of goods and services.

These Kenyan brokers, those who would normally connect importers and brokers to “friendlier” warehouses, have become increasingly irrelevant as the Chinese have grown less dependent on Kenyans as go-betweens for their businesses.

“They have taken over the entire supply and demand chain. Especially if they know you are Kenyan. The warehouses and the factories will guide you to a location back in Kenya where you can get the same goods you are seeking to import,” said a Kenyan businessman in Guangzhou who refused to be named for fear of victimisation.

Few Kenyans speak publicly about their woes in Guangzhou or Shenzhen, as they are nervous about offending the host country. In a recent interview with Daily Nation, the new Chinese ambassador to Kenya, Wu Peng, said that Kenyans should not fear being victimised or discriminated against while in China.

“I know there are many Kenyans in Guanghzou. They don’t have many problems as long as their status is legal. If you find any individual facing problems, you can bring it to the attention of our embassy, to my attention. We will try our best to help. However, we don’t want generalisations,” he was quoted as saying.

In Kenya, Chinese nationals are setting up businesses in droves because of sweetheart policies in Beijing, including export tax rebates of up to 16 percent; non-compliance of local tax laws; easy access to visas; and failure of the Kenyan government to come up with sound policies to protect the local small-scale market.

Kenyan traders must have a consolidated business permit (a trading license, an advertising signage license, a health certificate, a fire clearance license, a food hygiene certificate), pay value-added tax and withholding tax, and pay rent. This dramatically increases their overhead.

Chinese traders with business permits use Kenyans or their counterparts with permanent residency to register their commerce. They have set up godowns along Mombasa Road, Industrial Area, Hurlingham and along Outer Ring Road.

Others have set up kiosks along Luthuli Avenue to sell mobile phone accessories and CCTV cameras, along Sheikh Karume Road to deal in construction hardware and solar products, and in Gikomba Market to sell second-hand clothes, famously known as mitumba.

“Kenyans have always complied to every demand by the Chinese government to get a visa to China in order to engage in business. But the Chinese will come here with a tourism visa, set up a business, and the Kenyan government cannot lift a finger to protect small-scale traders,” says Mr Mutahi.

At Sheikh Karume Road, the presence of Chinese nationals selling electronic and solar items is a common sight. In one such building, local traders say they cannot cannot keep up with their Chinese competitors.

“On this floor, we have nine shops. He occupied one shop when he came. Now he has expanded to four other shops by driving out traders who were dealing with solar products because he is very cheap. Soon he will come for mine, and I will have no option. My goodwill to operate this facility was Ksh2 million. They are offering the landlord Ksh10 million for the same space,” says Pius Nzisa, whose shop directly stares at the two Chinese operating the expansive solar parts den.

Nyambura Ng’ang’a, who runs a shop off Luthuli Avenue, has not seen the cargo she imported in October 2017 as the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) confiscated her goods at the Mombasa port. She is one of hundreds of small importers left stranded after KRA refused to release goods worth Ksh12 billion as they were suspected of either being contrabands, substandard, or illegal.

Most small traders share containers that are cleared as single consignments. Unfortunately, once a container has been earmarked as holding counterfeit goods, it is caught in a multi-agency tangle comprised of the KRA, the Kenya Bureau of Statistics and the Anti-Counterfeit Agency.

Various trips to government offices have changed nothing. Neither have assurances by President Uhuru Kenyatta that their goods will be released with a total waiver on various taxes and fees.

Meanwhile, Ms Ndung’u’s Chinese competitors restock their warehouses and shop outlets regularly, as if the rules of the ports jungle apply only to Kenyan importers.

“If they say we are importing counterfeits, and the Chinese are flocking their stores with the same goods, what exactly do they mean? We have asked for an opportunity we point to them our respective stuck goods in order to ascertain their worthiness, but no one is willing to listen to us,” adds Ms Ndung’u.

Since 2016, KWITA has engaged government officials, including the Office of the President, to protect them in what became an increasingly bitter trade standoff, “yet nothing to this effect has been done by this government,” said Mr Mutahi.

National and local government officials did not respond to our efforts to contact them.

“Our issue is why can’t the government negotiate deals that will favour the common mwananchi instead of always selling Kenyans to the highest bidder. The government of the People’s Republic of China should negotiate for investors with large sums of money to invest in Kenya to partner with us and develop our country. Kenyan government should negotiate for Chinese people to travel to Kenya as tourist and enjoy the beauty that is in our country,” added Mr Mutahi.

“If at any point a Chinese person wishes to invest with Kenya, our government should have policies that protect local or foreign partnerships. Not on the basis of marriage or financial capacity but a mutually beneficial relationship between the Kenyan and Chinese person,” he said.

John Njiru, a Kenyan, is an award-winning financial journalist. He is an Aga Khan University Graduate School of Media and Communications Fellow for 2019.