The World Bank is sounding an alarm about the danger confronting low- and middle-income countries—particularly the poorest.

- Through its international Debt Report 2023, the lender says the overall debt-servicing costs for the 24 poorest countries are expected to balloon by as much as 39 percent in 2023 and 2024.

- This will shift scarce resources away from critical needs such as health, education, and the environment.

- Besides the steeper interest rates that all countries are paying on their debt, the poorest face an additional burden: the accumulated principal, interest, and fees they incurred for the privilege of debt service suspension.

The exact costs of that privilege will not be known until the data are reported later this year. But it is safe to say the costs will not be insignificant—and poor countries will need more global help to ease their debt than they are receiving now.

“Record debt levels and high interest rates have set many countries on a path to crisis,” said Indermit Gill, the World Bank Group’s Chief Economist and Senior Vice President. “The situation warrants quick and coordinated action by debtor governments, private and official creditors, and multilateral financial institutions—more transparency, better debt sustainability tools, and swifter restructuring arrangements. The alternative is another lost decade.’’

Surging interest rates have intensified debt vulnerabilities in all developing countries.

- In the past three years alone, there have been 18 sovereign defaults in 10 developing countries—greater than the number recorded in all of the previous two decades.

- Today, about 60 percent of low-income countries are at high risk of debt distress or already in it.

- Interest payments consume an increasingly large share of low-income countries’ export, the report finds.

More than a third of their external debt involves variable interest rates that could rise suddenly. The stronger US dollar is adding to their difficulties, making it even more expensive for countries to make payments. Under the circumstances, a further rise in interest rates or a sharp drop in export earnings could push them over the edge.

As debt-servicing costs have risen, new financing options for developing countries have dwindled. In 2022, new external loan commitments to public and publicly guaranteed entities in these countries dropped by 23% to $371 billion—the lowest level in a decade.

Private creditors largely abstained from developing countries, receiving $185 billion more in principal repayments than they disbursed in loans.

That marked the first time since 2015 that private creditors have received more funds than they put into developing countries. New bonds issued by all developing countries in international markets dropped by more than half from 2021 to 2022, and issuances by low-income countries fell by more than three-quarters.

New bond issuance by International Development Association (IDA)-eligible countries fell by more than three-quarters to US$3.1 billion.

- Multilateral creditors provided $115 billion in new low-cost financing for developing countries in 2022, nearly half of which came from the World Bank.

- Through IDA, the World Bank provided $16.9 billion more in new financing for these countries than it received in principal repayments—nearly three times the comparable number a decade ago.

- In addition, the World Bank disbursed $6.1 billion in grants to these countries, three times the amount in 2012.

“Knowing what a country owes and to whom is essential for better debt management and sustainability,” said Haishan Fu, Chief Statistician of the World Bank and Director of the World Bank’s Development Data Group. “The first step in avoiding a crisis is having a clear picture of the challenge. And when problems arise, clear data can guide debt restructuring efforts to get a country back on track towards economic stability and growth.”

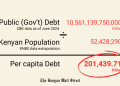

The report notes that IDA-eligible countries have spent the last decade adding to their debt at a pace that exceeds their economic growth—a red flag for their prospects in the coming years. In 2022, the combined external debt stock of IDA-eligible countries hit a record US$1.1 trillion—more than double the 2012 level.

From 2012 through 2022, IDA-eligible countries increased their external debt by 134%, outstripping the 53% increase they achieved in their gross national income (GNI).

Kenya faces looming Debt Crisis as its first Eurobond Matures in 2024 (kenyanwallstreet.com)